“…as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don’t know we don’t know. And…it is the latter category that tend to be the difficult ones.” – Donald Rumsfeld

When the then-acting United States Secretary of Defense uttered those enigmatic words during a news briefing on February 12, 2002, no one could have predicted the resonance that would later be felt in the digital humanities, a field yet undefined at that time. And yet, as “unknown unknown” methods for literary analysis have developed—such as computational literary studies (CLS)—enigmas have become prophetic, and the Digital Humanities continues to find itself divided along what Kathleen Fitzpatrick, in her 2011 article, “The Humanities, Done Digitally,” calls “an updated version of the theory-practice divide that has long existed in other quarters of the humanities.” This battle between “those who suggest that digital humanities should always be about making (whether making archives, tools, or new digital methods) and those who argue it must expand to include interpreting,” Fitzpatrick argues, contrasts the arbitrariness of the distinction between the two categories. She continues, “In fact, the best scholarship is always creative, and the best production is always critically aware.” Subjectivity aside, one can draw from these claims that when scholarship and creative practice is combined, the end result is typically a product that is greater than what could have been produced in either of the areas alone.

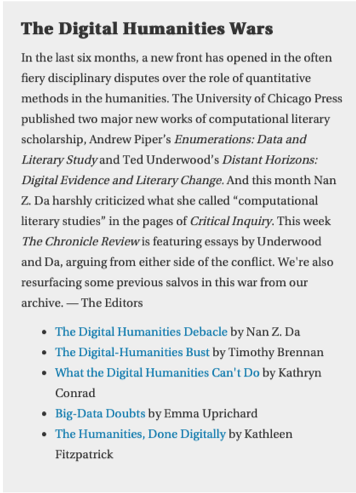

So why then does the expanding field of digital humanities continually find itself to be an imbricated mosaic of creative and scholarly practices attempting to clearly delineate and erect borders between fields of study and areas of specialization? Why does The Chronicle of Higher Education host a series (see Figure 1) that it describes as “The Digital Humanities Wars” in which it specifically invites contention? What is the benefit served in setting these up fields of study as working against one another, rather than together to promote a common cause?

Nan Z. Da seems to suggest that part of the reason for this is to ensure that computational processes to be included in the field of the Humanities need to follow the same rigor applied to other areas, involving peer review from parties who do not have a stake in the production of works associated with CLS. Da proposes, “Evaluating CLS means more than checking for robustness. It means starting with these questions: Has the work given us a concrete, and testable, channel for understanding the predictive mechanism that it has proposed? Does it ask an interesting question as literary criticism, and answer it without recourse to brute comparison?”

Ted Underwood, in another article of The Chronicle’s series, combats Da by stating “For many scholars, the humanities are defined not just by their subject domains, but by a specific set of methods, emphasizing qualitative description of selected case studies. If we start from this assumption, it will look like a definitional error to describe new quantitative projects as an expansion of the humanities.” For Underwood, the digital humanities must expand the way that it examines pieces of literature to make room for new practices and new modes of understanding.

Considering these two articles together, it becomes clearer that one side wishes to keep the humanities as they are in order to maintain the level of scholarly rigor associated with the academic approaches toward new material. In doing so, that side reveals an anxiety that the inclusion of practices not previously used will somehow degrade the other practices that are used in association. By letting in “science”, the “humanities” lose value. Across the schism is the belief that new practices offer a mode of examining literary material in ways that previously couldn’t be considered—something that seems like an intrinsically beneficial idea. Underwood even goes so far as to claim, “these interdisciplinary connections can create opportunities that work in both directions.”

So then what exactly seems to be the problem? If we remove our scholarly egos from the picture, the goal of literary scholarship is to find new methods of critique and analysis to use alongside older methods that are already known, then apply those methods to old and new sites of literary material to create a better understanding of that material, the media that presents that material, and the human experience/life/condition, is it not? The value in scholarship is not a finite resource—finding and accepting value in new modes of research does not inherently diminish previous modes of research.

As scholars, it is our job to, yes, question those modes when they arise, but we should not be creating artificial problems at the borders of our fields of study. Our very own Co-Director, Dr. Angel Nieves, offered some valuable insight into this topic. “Perhaps a way to end this,” he said, “is to consider that boundaries are very much what fields and disciplines are all about—discrete and measurable forms of knowledge that remain bounded in order to keep those who can’t speak, read, or write in those areas outside that community of practice or knowledge-making.”

Dr. Nieves illustrates a powerful point about the politics of boundary creation. All boundaries are politicized, and so must be critiqued. We need to be asking ourselves important questions about why and how we trying to dictate arbitrary boundaries, wherever they are encountered in life, like:

- Is this boundary natural, or is it constructed?

- What is the purpose of the boundary that is being created?

- What is being separated and placed in opposition, and why?

- Are these things/ideas/concepts/theories really at odds with each other?

- What are the beneficial or detrimental aspects of this boundary?

We hope that you have enjoyed our fall 2019 “Critical Inquiry” blog series and have found our articles to be useful and informative. We also hope that you will take the questions we have been discussing and apply them to your own research. In case you missed them, be sure to check out the previous posts in this series:

Until next time, peace, love, and DH!

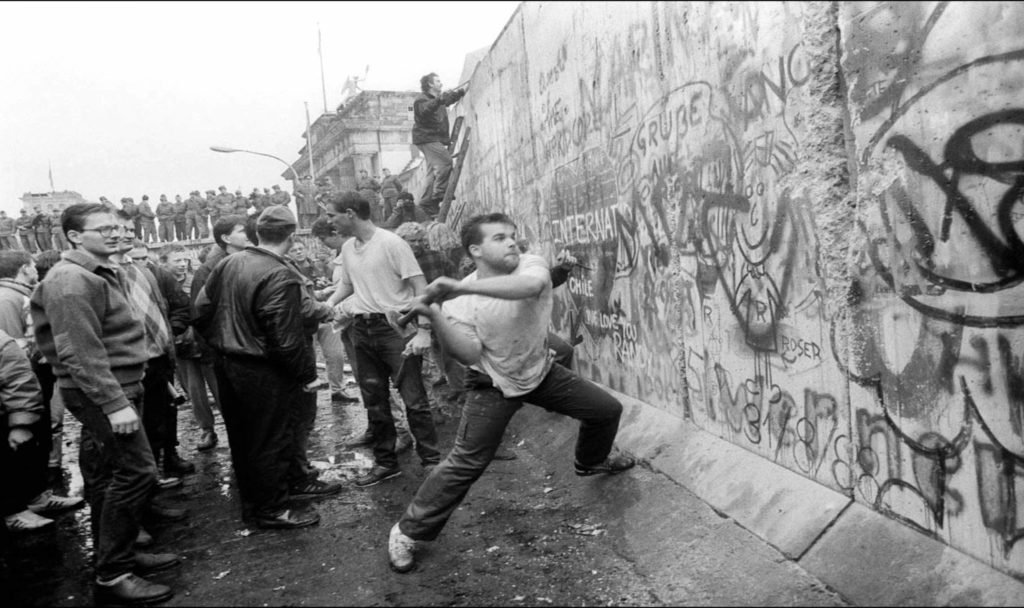

Top Image: Verso