The past—that monolithic nonentity that weighs so heavily upon our present situation. Our past, the past we adhere to and accept, is what defines who we are in many regards. The things we have done, mixed with the benefits we have been given and the actions forced upon us by others, have led us to our current position in life, whatever that may be. As a defining force of the now, it is necessary to ensure that our records of the past are updated alongside the technology used to archive them. As technology continues to expand in the ways that it can depict old and new media, new avenues for looking back are opening up in ways that allow us to perceive a different, or more accurate, past than we may have been taught.

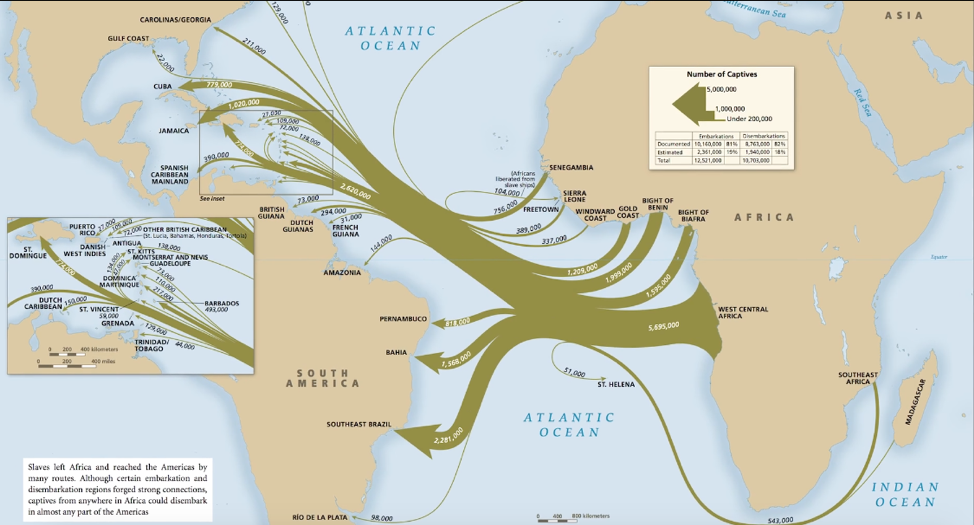

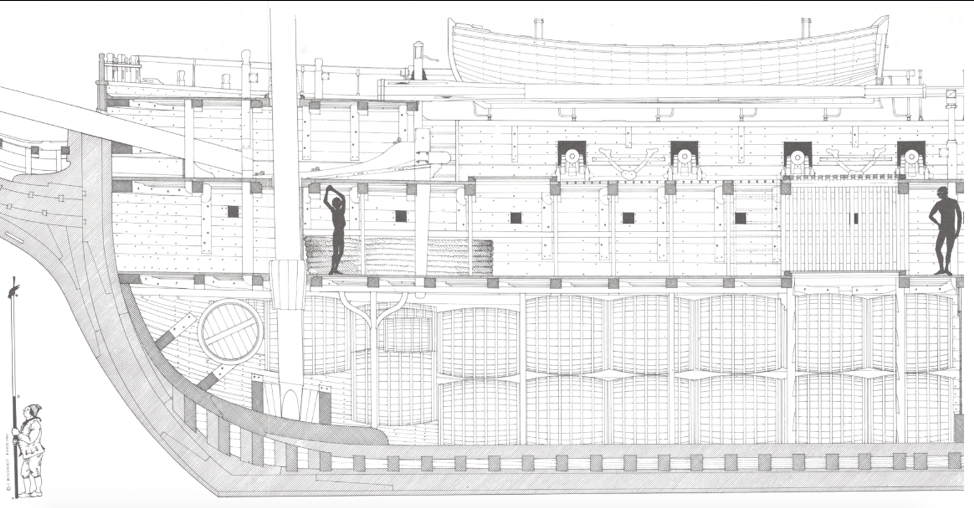

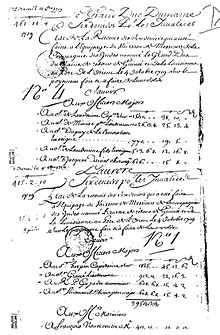

Dr. Nicholas Radburn, co-editor of “Voyages: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database,” working with a team of other scholars at Emory University, has created a 3D model of the 18th century French slave ship, “L’Aurore”. Radburn’s choice to use the ‘Aurore’ was a decision of limited berth—the plans used to build the ship are the only ones still known to be in existence, according to an article posted by the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). “When I was undertaking my doctoral research,” said Radburn, “I discovered that the flat images of slave ships really didn’t capture the realities of the trade. To address this problem, and as part of ‘Voyage’s’ recent redesign, I developed the 3D model of a slave ship in collaboration with the digital team at Emory.”

Viewers of the nearly five-minute video encounter a harrowing image of what conditions would have been like for the roughly 600 people that were enslaved and forcibly migrated to the Americas and what is now Haiti, where they were sold to coffee and sugarcane plantation owners. As the video progresses, the sense of crampedness filters through the screen and into the skin, leaving a sickening feeling in its wake.

Tools like this bring new life to static images, allowing students and educators alike to get a closer look at the horrible conditions forced upon an entire culture. Introducing this information into the digital realm helps to reiterate the necessity of continuing the scholarship about a turbulent past. “We are in a digital age,” says Radburn, “so this project was very much about using those tools to provide something better and more engaging.”

One critical question that we must ask ourselves about projects such as these pertains to the potential of reinflicting trauma upon groups who have not asked for these topics to be brought into the light once again. For some, the listing of the names of forced migrants, such as occurs within the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, can enact a replaying of traumatic pasts upon new recipients. As scholars, it is necessary for us to ask ourselves what harm our research may be causing, and how we can best abate the pain and suffering of previously wounded groups with our research.

In the case of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database however, there seems to be a strong argument that much good is happening as a result of potentially painful critical inquiry. According to an article by the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, the database may be helping to make the case for reparations more viable than ever before. “’Before this, scholars didn’t have an accurate database of the slave trade,’ said Brett Bobley, director of the office of Digital Humanities for the National Endowment for the Humanities, which, along with the Mellon Foundation, has awarded grant money to Emory for the website. ‘This is now the comprehensive resource.’”

By working with the communities whom the scholarship is depicting, the creators of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database established their intent to be both inclusive and considerate of the people involved. Through their actions, we can articulate some questions that likely aided in their critical inquiry.

- Are the methods being used to obtain the information necessary free from causing any further harm to the communities being studied?

- How can historical biases be identified and rectified when examining documents?

- How can we shed new light on identities that have been historically disparaged in a way that honors and respects the memory of those people?

Dive deep with us as we explore powerful questions of critical inquiry like these and more as the semester continues. The next post in this series will focus on the Library of Congress, Twitter feeds, China and the problems of limiting voices in the historical record.

If you missed it, be sure to check out the other pieces in this series:

Until next time, peace, love, and DH!