I wish I had learned about Digital History sooner. A professor introduced a great video that represented the dead and injured soldiers and civilians involved in WWII and I found the visual representation of the data fascinating. It put the large numbers into perspective. The site also had an interactive feature that was appealing and easy to use. It was seamless and didn’t seem dated like many websites that try to include historical breakdowns and information. To this day I share the site with my friends who are interested in WWII history.

Digital history comes in different shapes and forms, and the tools to create digital projects also differ. In the digital history class I am taking we have analyzed websites as users and as historians. Some sites merely copy data and text from books, disregarding the potential to represent data in different ways or to be interactive. I believe this is due in part to the lack of knowledge about different tools for making sites, as well as the belief that it can be difficult and require a high level of computer skill. I came into the class assuming that I would have to learn some computer coding, but instead we are using pre-programmed tools that allow us to input data such as text, numbers, and images, and receive a professional looking project. In class we have used Timeline JS and Storymap JS, both open source websites from Knightlab that allow the user to create visual representations of history and then embed those projects in their own website. They are free programs that certainly have their drawbacks, but on the whole they are easy to use. My biggest pet peeve was the lack of customization when it came to changing text size, font, and layout.

A comprehensive list of similar programs would be amazing, but it would have to constantly be updated which would require funding, time, and constant research to find the newest tools and sites available. This is one problem when it comes to teaching digital history; Tools are constantly changing. In one instance the provided instructions to “publish” our project, or make it viewable in a website, were outdated and we had to troubleshoot the website on our own. The physical books and articles were read were also out of date by the time we read them. This is no fault of the professor, but rather a commentary on the speed at which digital trends and tools change. Websites from the early 2000s look visibly dated, and books printed around that time are similarly dated.

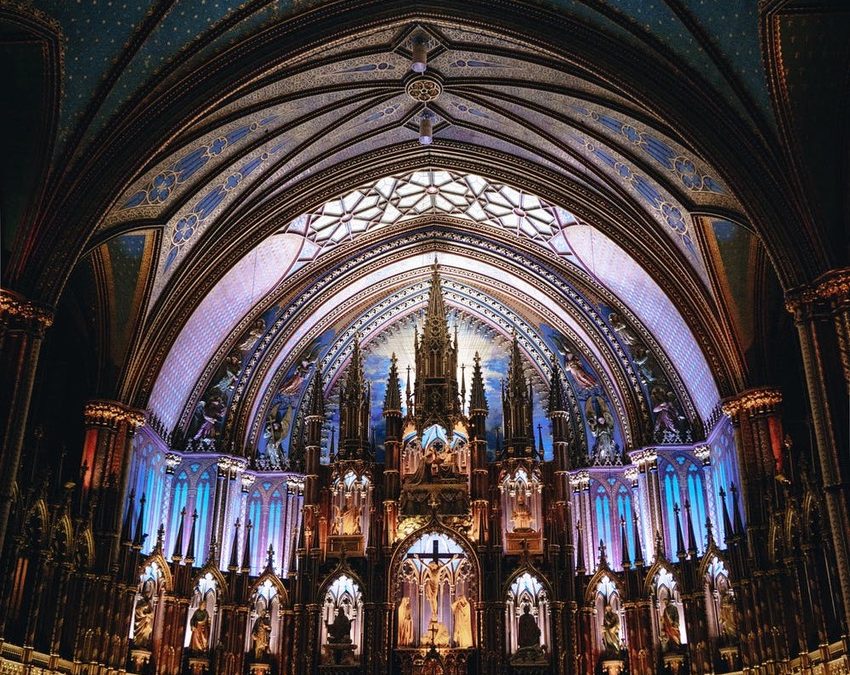

The recent destruction of Notre Dame has put digital history–specifically 3-dimensional scans–in the news. CNN and other news outlets have reported that a project by Andrew Tailon, an art professor, provide the best chance for a realistic reconstruction. He and his team scanned the building with lasers, in a “painstaking” process to create a digital, 3-D rendition. While the articles don’t refer to this as exactly ‘digital history’ I am hopeful that it will be regarded as such, and maybe introduce more people and students to the concept. Digital history is so much more than digitalizing books or photos and publishing them to the web. Digital history includes interactive websites that can show a 3-D rendition of a building. It can include interactive sites, or sites that show the progression of ships or armies in video format. It can bring history to life in a way that books lack.