Reflections about the digital humanities from a recent SDSU graduate

By Rose Rastbaf

I had registered for Dr. Pollard’s Spring 2019 Ancient Rome, HIST 503, expecting a curriculum akin to that of a conventional history syllabus: traditional reading assignments, essays, and research papers, with the most computationally advanced, technologically challenging requisite being but typing a few of the aforementioned tasks. I was consequently nonplussed, and in the interest of full disclosure, reasonably intimidated upon gathering that there would be a significant digital feature to the course. It was there and then that I was first formally introduced to the discipline of digital humanities.

I felt a wrench had been thrown into my plans. As a budding student, from the early years of childhood through adolescence, I had invariably found myself partial to subjects like literature, government and economics, and philosophy over those of STEM, as they are now widely called. The former came more easily to me, and I had a particular affinity for them as well. I thus pigeonholed myself as a “soft science” person early on in my academic career, sardonically deeming the “hard sciences,” as aptly-named, a proverbial no-go zone. They were mutually exclusive fields, I decided. One had aptitude either for one or the other. I actively sought to avoid them even as I began my collegiate studies, methodologically planning my schedule each ensuing semester, preferring to err on the side of caution, in the realm of familiarity and comfort.

It has been said that one meets their fate on the road taken to avoid it. Little did I anticipate, however, that the manifestation of a presumed personal nightmare in a presumed safe space, no less, would lead me down a rabbit hole of both intellectual pursuit and self-actualization as I would joyfully discover a newfound passion.

Our class’ foray into digital humanities began with an introduction to the programming language of HTML. We began practicing rudimentary coding, working our way up to advanced code. We then progressed to displaying data, similarly acquainting ourselves with the comparatively basic version of our first tool, an unidimensional historical timeline of the Roman Empire in our textbook, before transitioning to TimelineJS, its digital counterpart.

Stratified into small teams, my classmates and I tackled group projects utilizing the software, which served as preparation for the final project in as much as we grew accustomed to digital visualization at large and concurrently had the chance to cultivate an opinion on TimelineJS; whether we enjoyed it, and thereby, whether we wanted to employ it for our final.

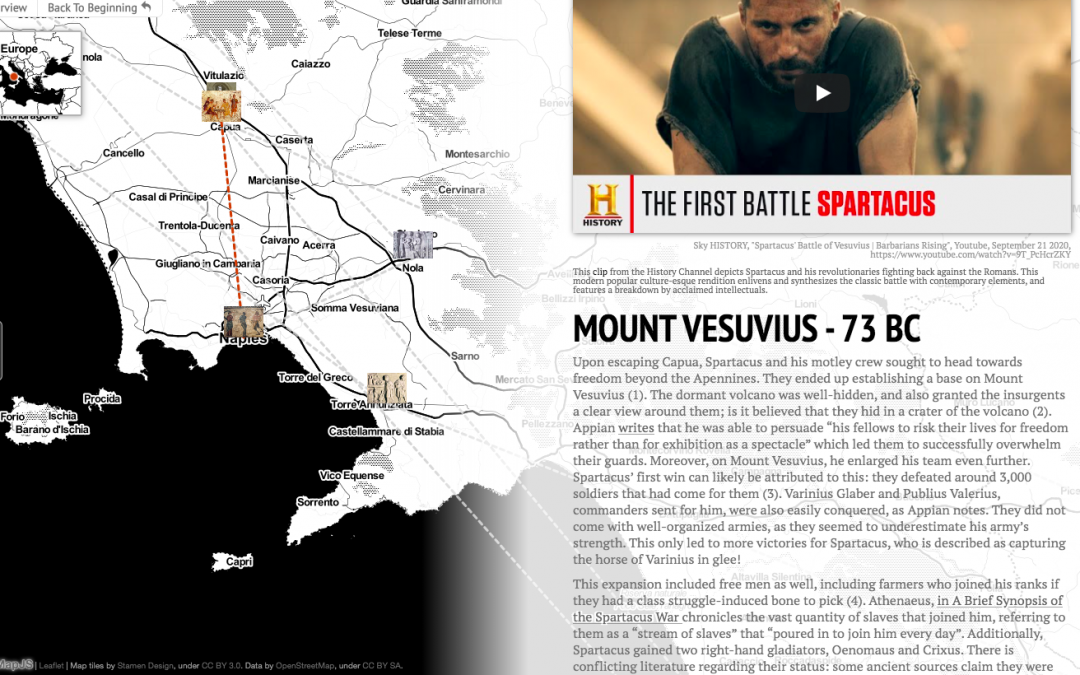

On that note, lastly, we engaged with StoryMapJS, which reconstructs the customary print map, quite literally bringing it to life. I had already determined I wanted to use it over TimelineJS for my final project ahead of commencing its respective group project, as I had been instantaneously drawn to the spatial functionality as opposed to a temporal mode.

I was decidedly pleased with the ultimate result, and above all relished the process of creating a StoryMap, the journey more so than the destination. Suffice it to say, the visceral emotion of having triumphed in a supposed indomitable area was exhilarating, and I had only experienced a mere corner of the digital humanities universe.

HIST 455, Digital History (Fall 2019), was an entire course dedicated singularly to analyzing and applying digital humanities. It had fairly recently become an option for the capstone requirement for the history major, giving the orthodox senior seminar some generous competition, and also signifying the increasing necessity and permeation of the subject matter. I would soon encounter this firsthand, evidenced by having to join and remain on a waitlist until the eleventh hour of the add/drop deadline to have a chance at taking the class in the first place, and subsequently when I would realize that I had unknowingly, and not too long ago at that, contributed to the speciality myself.

Dr. Nieves used an inverse pedagogy relative to Dr. Pollard, instructing us in working backwards from the final project as early as the first couple meetings of the term. With the help of the University Archivist, Amanda Lanthorne, we collectively toured the Special Collections & University Archives in the Malcolm A. Love Library, selecting a primary source from the department that spoke to us personally; this object of our choosing would form the basis of our final. We were likewise directed to choose between two means of rendering our argument: ESRI StoryMaps or a podcast.

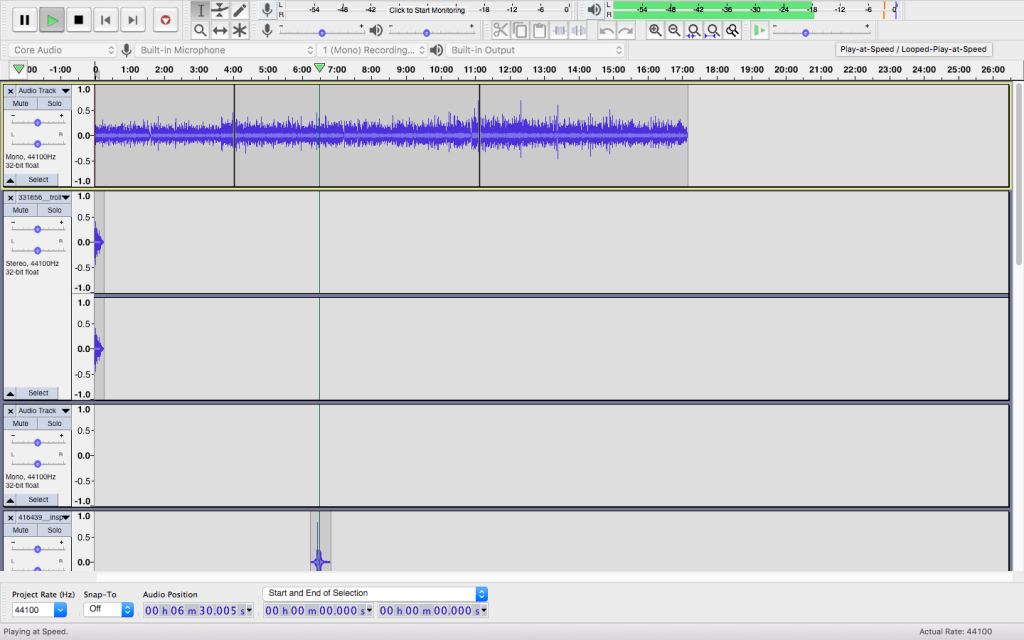

While continuing to meditate on our item and how we wanted to expound it, our class completed exercises in the Language Acquisition Resource Center, again in partners, reverse engineering digital history websites and evaluating digital scholarship, exploring interface design, gaming engines, apps, and virtual reality devices, absorbing the digital project life cycle, and finetuning our understanding of data, metadata, and visual and audio literacy.

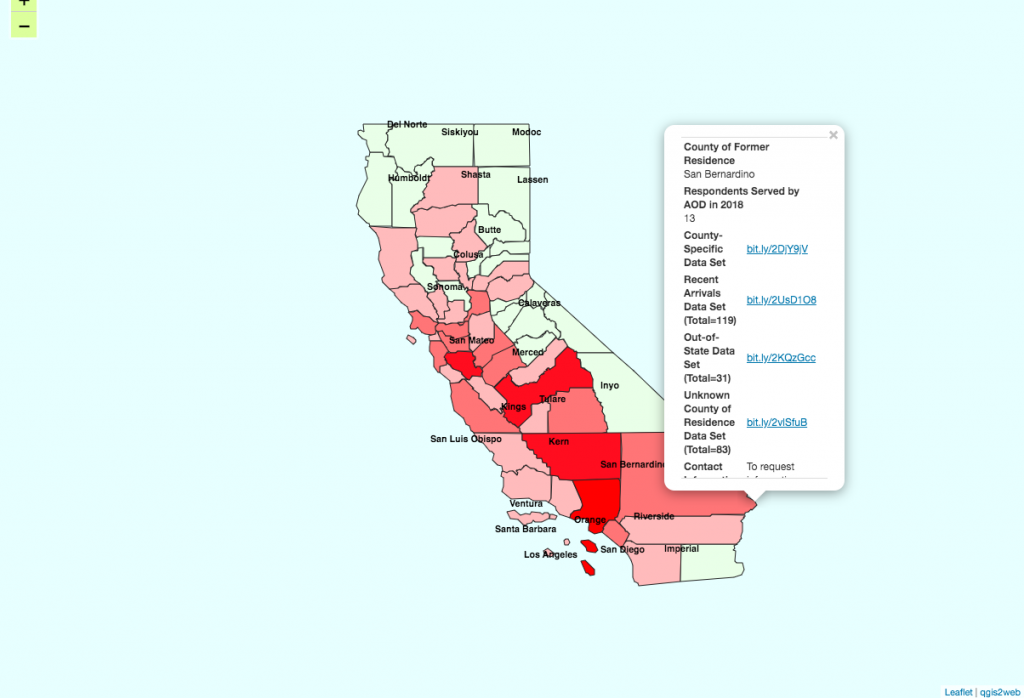

I had once more settled readily on which instrument to implement for the final project, this time even quicker as I had just used a mapping platform the past semester, and sought to branch out so as to take advantage of the opportunity to learn as much as I could, while I could. I indeed had chosen correctly: while perusing the ESRI software and its companion product arcGIS, I thought that GIS sounded familiar. It then dawned on me that I had used GIS a little over a year prior, during a formative internship at The Bar Association of San Francisco, which had marked one of the first steps of my professional career.

It was assuredly not a coincidence that digital humanities had been playing an active role in my life the whole time, before I knew it even existed, and throughout such a pivotal milestone at that. This revelation also proved just how momentous and practical the discipline is: there is no stronger testament to “real world” applicability, after all, than actual use in the workplace! Now more than ever, as we live through the most digitally connected era humankind has ever known, the Information Age, which has been heightened further yet by the global pandemic, it is unequivocal that graduating students should have exposure to digital humanities. They may even find it has already crossed their path!

Rose Rastbaf, Class of 2019, was a Political Science & History major